There is much about organ donation that the public has not been told. Informed consent to any medical procedure (consent based on truthful and complete disclosure of all relevant information and free from coercion) is the ethical cornerstone of medical decision making. However, anyone applying for a driver’s permit or license, regardless of age, is asked to consent to organ donation with little or no accurate information offered. And, family members (of seriously injured or disabled patients on ventilators) frequently report being subjected to heavy pressure from organ procurers eager to obtain organs.[1]

Here are answers to questions about organ donation—questions you may not even know you should ask.

What does “Give the Gift of Life” mean?

“Give the Gift of Life” is a marketing slogan designed to induce people to sign organ donor cards. Organ donation is always to be considered a gift, not a duty or an obligation. However, this gift should never harm or cause the death of the giver. We must be wary of the many dangers present in a culture which values certain lives more highly than others.

Is it morally licit and safe for a healthy person (frequently referred to as a “living donor”) to donate a paired organ or part of an organ for the welfare of a relative, friend or stranger?

The answer to this question is more complicated than a simple “yes” or “no.” Certainly, a “living donor” makes a sacrificial gift of love. However, each of us has a moral responsibility to protect and preserve our own health and life. Both medical advice and moral guidance are necessary when considering this type of organ donation.

Single kidney donation is the most frequent “living donor” procedure. Other organs that may be taken are one of the two lobes of the liver, a lung or part of a lung, part of the pancreas, or part of the intestines. The donor faces the risk of an unnecessary major surgical procedure and recovery. Sometimes there are adverse psychological outcomes or other consequences such as reduced function, disability, or problems getting medical insurance coverage at the same level and rate as previously. A small percentage of “living donors” die as a result of donation.[2] All of these risks must be weighed along with the benefit the donated organ may be (no guarantee here either) to the organ recipient.

When may organs be taken from Patient A to give them to Patients B, C, D, etc.?

The vast majority of organs for transplant are taken from patients who have been declared dead. A declaration of death does not always mean that the patient is certainly dead. Morally, organs and tissues may be taken from Patient A only after death is certain. (This “dead donor rule” is one of the basic ethical principles guiding organ donation.) Furthermore, donation must be voluntary, meaning that either Patient A or someone legally entitled to donate Patient A’s organs has given informed consent.

Are organ donors certainly dead before their organs are removed?

The simple answer is “no.” Before organ transplantation was possible, physicians cautiously determined death, based on irreversible cessation of both cardiac and respiratory functions, in order not to treat the living as dead. Today, “brain death” is declared while a patient still has a beating heart and is breathing (albeit with the aid of a ventilator) because removal of vital organs must be done before they begin to deteriorate due to loss of blood circulation. Vital organs are useless if physicians wait to remove them until they are certain the patient is dead.

Tissues (such as bone, skin, tendons, cartilage, connective tissue, corneas, and heart valves) do not require continuous circulation of blood to remain useful for purposes of transplantation. Therefore, tissues may be taken up to several hours after death is certain.

If “brain death” is not death, what is it?

“Brain death” is a legal fiction. In 1968, a Harvard Medical School Committee met to define “brain death.” Their report begins: “Our primary purpose is to define irreversible coma as a new criterion for death….Obsolete criteria for the definition of death can lead to controversy in obtaining organs for transplantation.”[3] The Committee did not argue such patients are really dead.

The insurmountable moral and legal problem is that stripping living patients of their organs is murder.

State laws defining “brain death” (based on the Uniform Determination of Death Act) free surgeons from legal liability when they remove organs from patients who are not dead yet. Consider:

- A person can be pronounced “brain dead” while he or she has a beating heart, as well as normal pulse, blood pressure, color and temperature. All signs of life.

- “Brain dead” patients’ wounds heal. “Brain dead” children grow. “Brain dead” pregnant women, kept alive for extended periods, gestate and deliver healthy babies and produce milk. All signs of life.

- A “brain dead” organ “donor” is given a paralyzing drug to prevent squirming and grimacing when the incision is made to remove organs. Even paralyzed, his or her pulse races and blood pressure shoots up. Dead people don’t react to being cut.

Many experts have challenged the concept of “brain death.”[4]

Has anyone ever recovered consciousness after being declared “brain dead?”

Numerous accounts of patients who have recovered after a firm diagnosis of “brain death” demonstrate that “brain dead” patients are not certainly dead. Here are two cases.

Zack Dunlap, a 21-year-old Oklahoman, flipped over on his 4-Wheeler and suffered catastrophic brain injuries in November 2007. Thirty-six hours after his accident, doctors at United Regional Healthcare System in Wichita Falls, Texas, declared him “brain dead.” Preparations to harvest his organs were underway when friends and relatives gathered to say their final goodbyes. His cousin, a nurse, wanting to make certain, scraped his pocket knife along the bottom of Zack’s foot. Zack jerked his foot away. Just months later, Zack was walking and talking. Zack recalled hearing the doctor say he was dead and being “mad inside” but unable to move.[5]

Steven Thorpe, a British 17-year-old, suffered horrific injuries in a multi-car accident. Four doctors declared him “brain dead.” Doctors asked his family to consider donating his organs before his life-support was turned off. The family sought a second opinion from a neurologist who detected faint brain waves. Seven weeks later, Steven was discharged from the hospital having made a near-full recovery. In 2013, at age 21, now an accountant trainee, he spoke to the media for the first time: “Hopefully (my experience) can help people see you should never give up. My father believed I was alive—and he was correct.”[6]

Must a person be declared “brain dead” in order to be used as an organ donor?

No. Donor eligibility has been broadened to include another group of people who are not dead yet—patients on ventilators whom doctors label “hopeless” or “vegetative.” New rules were established to permit “donation after cardiac death” (DCD) because more organs were wanted to satisfy increasing demand and decisions to withdraw life support have become so easy and private.

What is “donation after cardiac death?”

A patient, family or surrogate agrees to have the ventilator turned off and a “do not resuscitate” order written, then gives consent to organ donation. When (or if) the patient’s pulse can no longer be detected, the organ retrieval team waits only 75 seconds to 5 minutes to declare “cardiac death” and begin organ removal. Haste is essential to ensure healthy organs. The donor may be given an anesthetic just in case the team acts too quickly. No one would consider a patient “dead” whose heart had arrested for a mere 5 minutes or less—that is, unless his organs are deemed more valuable than his life.

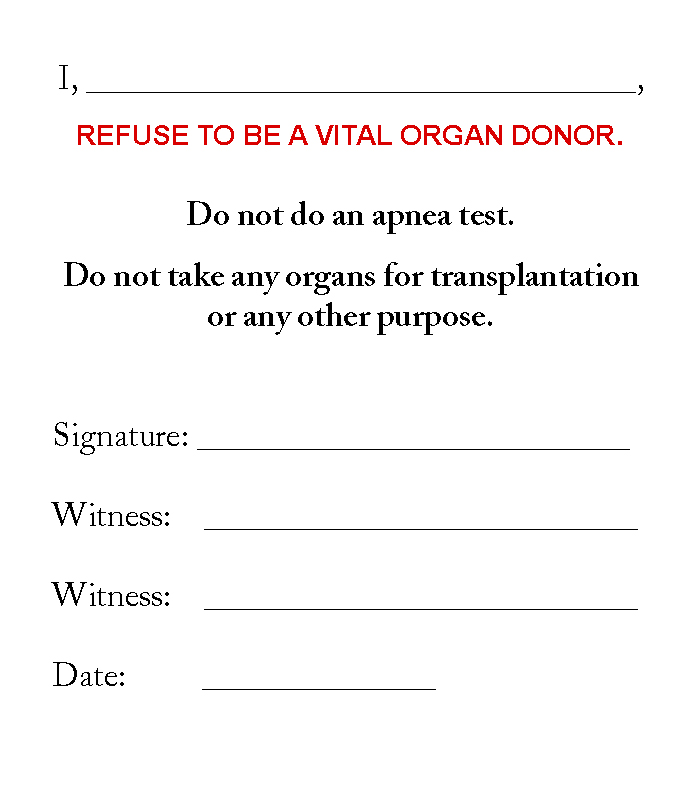

Should I refuse to be an organ donor?

Yes, for the reasons stated above and because the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA), as revised in 2006 and since adopted by most states, allows for patients who have never consented to be organ donors to be considered “prospective” donors unless they explicitly refuse. This means, if you have not explicitly refused to be an organ donor, you may be subjected to potentially harmful measures done solely to preserve your organs for transplant or to determine if you are “brain dead.” These things can be done without your family’s knowledge or permission. Your family may be left “in the dark” until asked for your organs.

The PHA suggests you carry an Organ Donor Refusal card at all times. Call (651) 484-1040.

|

|

|

About the author: Julie Grimstad is the chair of Pro-life Healthcare Alliance and director of Life is Worth Living, Inc.

References

[1] “No ‘moral certainty’ that brain death is really death: prominent Catholic ethics professor Brugger,” LifeSiteNews, 2/04/2011

[2] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, www.organdonor.gov

[3] Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School, “A Definition of Irreversible Coma,” Journal of the American Medical Association, 8/5/1968, Vol. 205, No. 6

[4]Examples:

“‘Brainstem Death,’ ‘Brain Death’ and Death: A Critical Re-Evaluation of the Purported Equivalence,” Alan D. Shewmon, MD, 14 Issues in Law & Medicine, 1998-1999.

“The Dead Donor Rule and Organ Transplantation,” Robert D. Truog and Franklin G. Miller, New England Journal of Medicine, 2008:359:674-675

Beyond Brain Death: The Case Against Brain Based Criteria for Human Death, Eds. Michael Potts, Paul A. Byrne and Richard G. Nilges, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht 2000

“Brain Death is not death,” David W. Evans, MD.

[5] NBC News Dateline, 3/23/2008, as well as numerous other reports

[6] “Steven Thorpe, British Teen Who Was Declared Dead By Doctors, Makes Miracle Recovery,” Huffington Post, 7/30/2013