Recently, I had reason to go look through through the collection of book reviews I’ve written over  the years, searching for one on Karen Ann Quinlan’s mother’s autobiography. I have resurrected that review and reprint it in this edition of the PHA Monthly for two reasons: (1) The 1976 Karen Ann Quinlan “right to die” case is often misrepresented as a case of physician paternalism versus a patient’s right to refuse unwanted, overly zealous medical treatment. I’d like to set the record straight. (2) A recent court decision confirms, once again, the prediction–by those who, in 1976, lamented the court’s decision and disagreed with its reasoning–that the decision in the Quinlan case would have far-reaching grave consequences.

the years, searching for one on Karen Ann Quinlan’s mother’s autobiography. I have resurrected that review and reprint it in this edition of the PHA Monthly for two reasons: (1) The 1976 Karen Ann Quinlan “right to die” case is often misrepresented as a case of physician paternalism versus a patient’s right to refuse unwanted, overly zealous medical treatment. I’d like to set the record straight. (2) A recent court decision confirms, once again, the prediction–by those who, in 1976, lamented the court’s decision and disagreed with its reasoning–that the decision in the Quinlan case would have far-reaching grave consequences.

the years, searching for one on Karen Ann Quinlan’s mother’s autobiography. I have resurrected that review and reprint it in this edition of the PHA Monthly for two reasons: (1) The 1976 Karen Ann Quinlan “right to die” case is often misrepresented as a case of physician paternalism versus a patient’s right to refuse unwanted, overly zealous medical treatment. I’d like to set the record straight. (2) A recent court decision confirms, once again, the prediction–by those who, in 1976, lamented the court’s decision and disagreed with its reasoning–that the decision in the Quinlan case would have far-reaching grave consequences.

the years, searching for one on Karen Ann Quinlan’s mother’s autobiography. I have resurrected that review and reprint it in this edition of the PHA Monthly for two reasons: (1) The 1976 Karen Ann Quinlan “right to die” case is often misrepresented as a case of physician paternalism versus a patient’s right to refuse unwanted, overly zealous medical treatment. I’d like to set the record straight. (2) A recent court decision confirms, once again, the prediction–by those who, in 1976, lamented the court’s decision and disagreed with its reasoning–that the decision in the Quinlan case would have far-reaching grave consequences.

During the 1960s and 70s, as a young nurse, I did not see physician paternalism (i.e., authoritarianism) so much as I observed doctors faithful to the Hippocratic Oath who respected the sanctity of life and the dignity of every patient. Back then, when we were sick, we found it consoling to have a doctor caring for us who could be trusted to use his knowledge and skills to preserve our lives. The physician-patient relationship was based on mutual respect.

It was the “right to die” movement’s claim, however, that many patients, against their will, were being kept alive endlessly on machines by paternalistic physicians. This canard was repeated over and over again until people began to believe it. This was a ploy to gain social and legal acceptance of the “right to die” by urging people to sign Living Wills in order to refuse “unwanted” life-sustaining medical treatment.

Perhaps there were instances where doctors were overly zealous in treating some patients (though I did not see it), but it was hardly a problem that needed to be solved by legalizing the “right to die.”

The attorney representing Karen Ann Quinlan’s parents was Paul W. Armstrong. He was recently in the news again as the judge in another “right to die” case. Superior Court Judge Paul Armstrong (Morristown, New Jersey) ruled on the case of a 29-year-old, severely anorexic psychiatric patient. He decided that this young woman could not be given artificially administered nutrition against her wishes.

Anorexia is a psychiatric disorder in which a person literally starves herself and which causes her to refuse treatment, knowing this will cause death.

Paul Armstrong, the first U.S. attorney to defend a patient’s “right to die” in court, now, as a judge, has granted a mentally ill person’s desire to die of her disease, that is, to die of starvation while receiving palliative care to keep her comfortable. This is euthanasia (by omission) presided over by physicians. Judge Armstrong just took us a giant step closer to physician-assisted suicide for psychiatric patients.

The following book review (mentioned in my introductory paragraph) was originally solicited by American Life League and published in ALL’s Celebrate Life magazine in 2005 or 2006. (I’ve forgotten the exact date).

Karen Ann’s Mother Remembers:

MY JOY, MY SORROW

By Julia Duane Quinlan

St. Anthony Messenger Press (2005)

A book review by Julie Grimstad

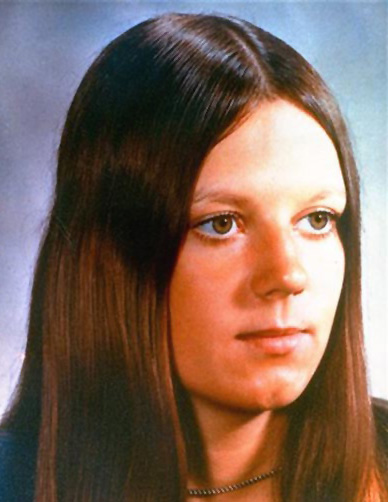

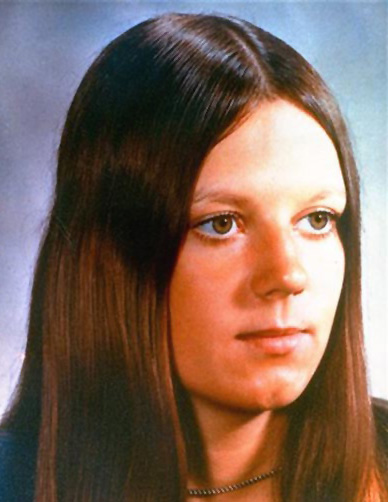

MY JOY, MY SORROW is Julia Quinlan’s autobiography woven around the story of the touching and tragic life and death of her daughter, the young woman at the center of the first “right to die” court case: In the Matter of Karen Quinlan, An Alleged Incompetent.

On March 31, 1976, the Supreme Court of New Jersey appointed Karen’s father, Joe, as her guardian and concluded that he could assert her “right of privacy,” thus granting him authority to seek withdrawal of her “life-support system.” Subsequently, Karen was weaned from a ventilator, but unexpectedly clung to life for nearly 10 years. She finally succumbed to a bout of pneumonia for which “No antibiotics were administered.”

In spite of its overly sentimental style and numerous grammatical errors, the book holds one’s attention. The personal perspective and intimate details, which only a mother could supply, will interest readers who want to know what really happened to Karen Ann Quinlan and her family. As Mrs. Quinlan says, “Others may have written about it, but they did not live it.”

For those interested in history, the author accurately recounts the many ways in which the Karen Quinlan case has had worldwide impact. Unfortunately, Mrs. Quinlan uses this opportunity to promote the agenda of the “right to die” movement, seemingly unaware that she is advancing the “culture of death” which Pope John Paul II urged all people of good will to resist. The frequent mention of the Quinlan family’s Catholic beliefs and Christian ethics is misleading, making this a dangerous book for the unwary.

Referring to April 15, 1975, the date Karen was admitted to Newton Memorial Hospital in an unconscious state, her mother writes in the Introduction, “Despite what many people say or believe, my beautiful, vivacious daughter died that night. Yet her withered body lived on for ten years.” That chilling description of Karen echoes the dehumanizing language frequently used to justify killing in the name of compassion.

While Karen was still alive, Joe and Julia Quinlan appeared on television in France, Belgium and England “with doctors who talked openly about euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide.” Later she writes, “Joe and I strongly disagreed with physician-assisted suicide,” but makes no such disclaimer about euthanasia. The Quinlans also spoke at many Death and Dying Conferences, sharing the podium with other heroes of the “right to die” movement such as Patricia Brophy and Pete Busalacchi. Mrs. Brophy, with court permission, presided over the dehydration and starvation death of her husband Paul in 1986. Mr. Busalacchi did the same to his daughter Christine in 1993. Julia Quinlan makes no distinction between removing a ventilator and withholding food and fluids. She states, “We all had one thing in common: We had to fight for the right of our loved one to die in peace and with dignity.”

The most profound tragedy is that Julia Quinlan, devout Catholic, believes, “The New Jersey Supreme Court decision on March 31, 1976, was a gift to humanity.” She proudly notes, “Today I concentrate on the benefits that we have all received from this landmark decision. It was there for the hundreds of cases that followed.” Indeed, the first “right to die” case did set the stage for untold numbers of people like Terri Schiavo to be intentionally killed by withholding from them the basic necessities for sustaining life. Ask Terri’s devout Catholic parents if the Quinlan legacy is a gift or a curse.